[From the Archives] Is Adventure a Thing of the Past?

Some thoughts on discovery, overcoming pessimism, and feelings of claustrophobia in a heavily populated world.

An excerpt from An Anthropology of Wandering: How Adventure Can Alleviate a Fearful Culture

Greetings fellow wanderers,

Today I am republishing another post from the archives. As Those Who Wander has surpassed 700 subscribers, I am grappling with the fact that most new subscribers may not have access to or be familiar with some of my initial writings. With 99 posts in the archive, I want to expose these paywalled posts to newcomers.

If you have been enjoying these ramblings on travel, adventure, and anthropology, please consider supporting my writing, which grants you full access to everything I’ve written on Substack, including excerpts from my upcoming book. In addition, the proceeds will go toward publishing and promoting my forthcoming book ‘An Anthropology of Wandering: How Adventure Can Alleviate a Fearful Culture’. The book is a first-person account of backpacking the Appalachian Trail that dives into anthropology, travel, fear, and the meaning of adventure in culture and society. If you love social science, adventure, and travel, this book will be for you. Stay tuned for more updates.

Lastly, Substack recently enabled an exciting new feature on their app—text-to-speech for all your favorite posts! You can now listen to anything published at Those Who Wander just like a podcast. And it’s incredibly simple:

Navigate to the post you want to listen to.

Click the play button in the upper right-hand corner of the screen.

Voilà!

Thank you to everyone who has subscribed and supported my work thus far. Cheers! -JSB

Now onto today’s archived post, Is Adventure a Thing of the Past?

“I’m afraid the day for this sort of thing is rather past…The big blank spaces in the map are all being filled in, and there’s no room for romance anywhere.”

-Arthur Conan Doyle, The Lost World

Something quite extraordinary has occurred very recently in human history. For thousands of years (and millions if we include our extinct hominid cousins) our minds have always looked beyond the horizon from a perspective that found comfort in the knowledge that there would always be new lands to discover and explore be it for the game animals for food, resources, or maybe just the sheer thrill of a quest. When land became exhausted and devoid of its natural wealth, we could always rest assured that somewhere “out there” we could search, find, and settle greener pastures. Even as recently as the mid-nineteenth century in the United States, people feeling constrained by the crowd could find solace by echoing the favorable, albeit male-centric, slogan of westward expansion, “Go west, young man!”

Consider frontiers for a moment. What comes to mind when we hear the term frontier? Many of us with a Western-centric education tend to think of the frontiers of bygone adventurous eras like that of the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries’ Ages of Discovery and Exploration; the 18th and 19th centuries, when manifest destiny was prophesized and subsequently “fulfilled” and the West “closed” and “tamed”; or of our current century’s resurging trend in space exploration, the “space frontier.” We think of Alaska as the “final land frontier.” We view places abroad like the Amazon, parts of India and Africa, and the Indonesian islands as the last bastions of indigenous or, more humorously, “lost” tribes (as if they’ve been wantonly wandering the forests like zombies desperate for global contact and attention).

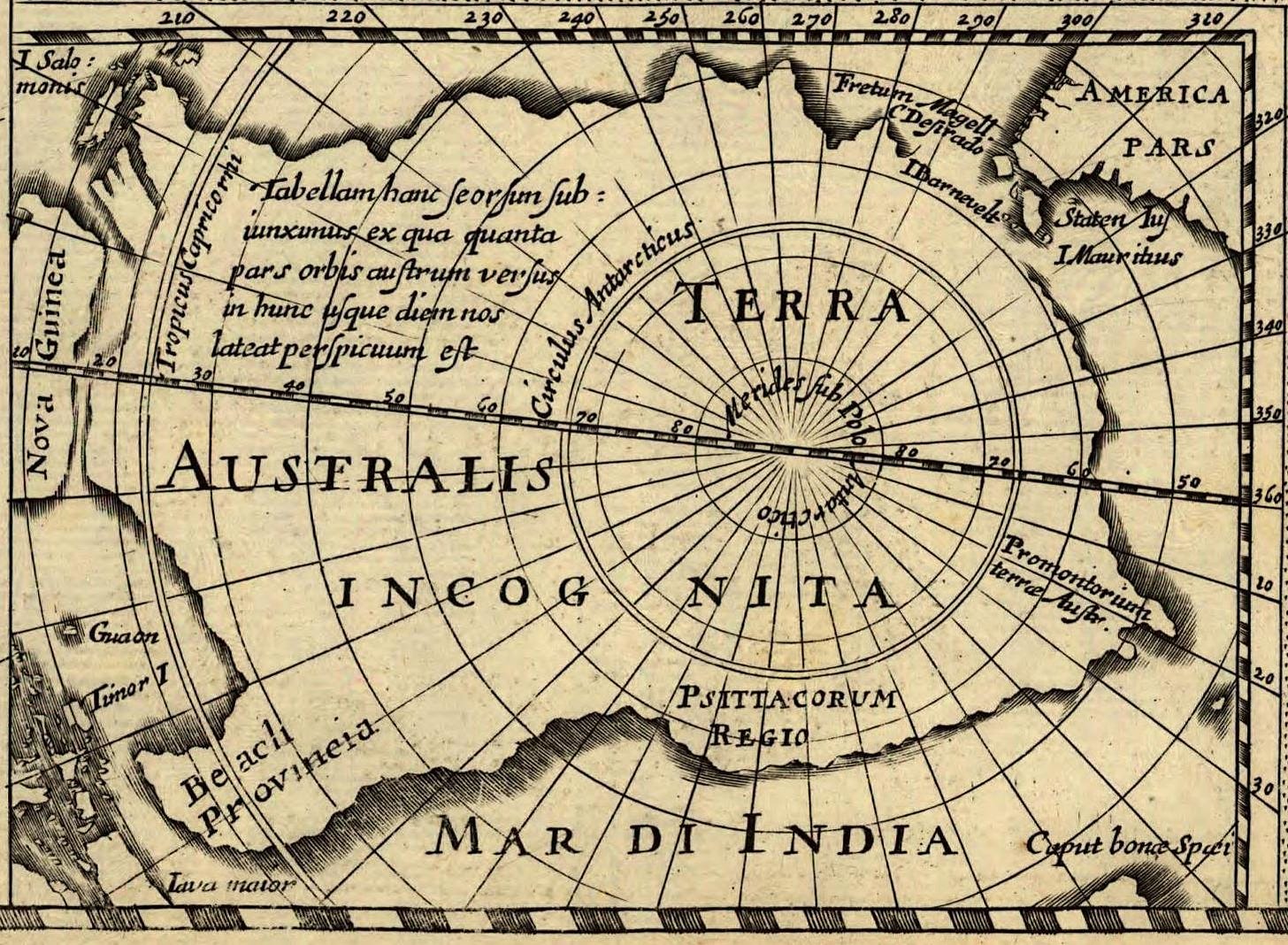

The term frontier isn’t used to refer to a place anymore, but is now a term of history (except for the eternal frontier of space). A frontier implied a divide between known and unknown, but this has come to an abrupt end. The terrain and seas on the maps of Earth today no longer read terra incognita or mare incognitum, Latin for “unknown land” and “unknown sea,” respectively. This isn’t to imply that these lands were truly unknown, given how many indigenous peoples inhabited these regions for millennia before cultures with cartography showed up on the scene. Nevertheless, we’ve come to a time where we have categorized and given a name to every tract of land, waterway, and ant hill on this planet. In addition, it has become international custom, under United Nations initiatives, to “freeze” borders in a laudable attempt to curb the most common and long-running source of conflict and violence: territorial disputes.

So, in some sense, we’ve become bitterly accustomed to viewing the world as wholly known and inactive in terms of future exploration and discovery. We may lament as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Professor Challenger in The Lost World,

“I’m afraid the day for this sort of thing is rather past…The big blank spaces in the map are all being filled in, and there’s no room for romance anywhere.”

The same was true for the aspirations of Joseph Conrad’s Charles Marlow in Heart of Darkness, where his idolized “blank spaces…had got filled since my boyhood with rivers and lakes and names. It had ceased to be a blank space of delightful mystery—a white patch for a boy to dream gloriously over. It had become a place of darkness.”

In one way or another, many of us have the notion that our world has been circumnavigated and explored extensively in the past. The land has been meticulously chopped out and squared by our surveys for centuries, and the enterprise of private property heavily restricts our mobility. We now must compete with our dollars to gain a smidgen of land to call our own. The United States Geological Survey (USGS), in its victorious war against blank spaces, has an endless supply of topographic maps that we are free to purchase or download so we can know the exact contour of the ground at any location and any resolution of the earth’s formations and every point, line, and polygon that are the scars of our civilization.

For those of us burning with a desire for an adventure into the unknown, we gain an unfortunate and dismaying sense that Earth today is already long-discovered, staked, and claimed—although the remaining two-thirds of the planet is water and remains largely unexplored. But to be fair, we are land creatures who enjoy our air, and the crushing weight of miles of the ocean makes it understandable why most of us like to keep our heads above the water.

We know footprints have already patterned the dead lunar surface. We know satellites clutter and circle our globe like sleepless sentinels. We know that several unmanned space probes are now doing our bidding in interplanetary and even interstellar space. The disquieting end of this is that we know the vast majority of us are likely bound to our modest little rock in space for many centuries to come (pending Elon Musk’s Red Planet migration attempts). What’s more, population trends and land regulations seem to be stifling our ability to move and feel some semblance of freedom. The world is metaphorically shrinking on us, and it can feel oppressively claustrophobic at times as global population density has skyrocketed in a short period relative to human existence on the planet.

Our culture occasionally attempts to uplift us. When we become entranced by movies, or listen to or read the eloquent words of those passionate about the vision of our future, the effects are often exciting and uplifting. Many of us are deeply inspired by scenes from epic movies and poetic musings by Carl Sagan, Neil DeGrasse Tyson, and so many other brilliant scientists who deliver beautiful discoveries and insights through TED talks, podcasts, and documentaries. But what happens to us, their captivated audience, after the closing credits end and the clapping hands and jubilant voices subside and fall to silence? Where does that leave the viewer after his or her catharsis? What happens to all that initial inspiration and motivation instilled in us? Do we immediately pack our bags and head out for our dream adventures or act on that inspiration? A few of us may well be able to retain that adventurous feeling and finally push ourselves out into the world to live our envisioned journeys, but this is rare. Very few of us, however, become engaged and enabled this way.

Many of us are unfortunately quickly swept up and ensnared by the pessimism so prevalent in our culture that works to diminish our enthusiasm and wanderlust. The harsh reality quickly sets in: Unending work won’t allow such a trip; the money isn’t there; surmounting bills leave us distraught; there’s not enough time to get in shape; there’s social unrest “over there” and it’s probably too violent anyway. We may even get the sorrowful feeling that it won’t be me who places my foot on the moon first, it won’t be me who makes the voyage, those days are long gone and my only means of feeling such thrills and emotions is indirectly through films and novels so why bother, why not forget about it?

There is much in this world that often washes in and cripples our grandest dreams and desires. It happens to all of us. Cynicism and nihilism are all but too frequent in our media and culture. The weight can seem unbearable. So for most of us, we return to the theater or the novel or to the TED talk to reclaim this supplemental feeling of adventure, only to repeat the process all over again. How often have we succumbed to this kind of complacent attitude? Is adventure a thing of the past?

On second thought, doesn’t having this outlook give the misguided impression that the world is changeless? Is something actually tainted or taken away from us if someone else has already been somewhere and done something we desire to do? This is fully understandable. I, too, felt something like this when first thinking about hiking the Appalachian Trail. I asked myself, “Why even do this? So many others have already done this. What’s the point?” The same feeling came to me when thinking of writing a book: “There are perhaps hundreds of books on the Appalachian Trail and adventure out there already, who’s going to bother reading this?” But I, fortunately, came to realize just how narrow-minded, unimaginative, and defeatist that attitude was.

I’ve come to appreciate that the Appalachian Trail, and all aspects of life, are so incredibly dynamic and variable. There’s an old saying, certainly well-worn by now, attributed to the pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus, that one cannot step foot in the same river twice. This is a concept that applies not only to the Trail but to all areas of time and place. Rivers, trails, and life are equally fluid and actively changing. We, too, are not a static thing, but a process. We are ever so slowly moving through time, but it moves so slowly that we fail to notice all the subtle changes occurring around us and within us. To be fair, particles shifting at the atomic scale aren’t exactly intuitive nor all that interesting to most of us. Nevertheless, we too easily become absorbed into the humdrum normalcy of life. It’s difficult to see sometimes that every detail of existence we experience today will be, in some form, either subtly or dramatically, altered tomorrow. We’re all fundamentally aware that things change, and much is unpredictable. We wouldn’t look both ways to cross the street if we weren’t that way.

To be sucked in by the poor nihilistic logic that tells us that nothing is new and that it’s been done before is demotivating and debasing to one’s creativity. After all, “Creativity,” as the anthropologist and well-rounded explorer Wade Davis deems, “is not the spark of action, it’s a consequence of action.” We become more creative in the aftermath of our initial plunge into the unknown. We can’t afford to sit around and wait for creativity to tap us on the shoulder to get us going. The trick is making the first leap. That someone else has done something you desire to do means very little because you haven’t experienced it yourself. And once we experience something remarkable that others have also experienced, we become more relatable to others: We experience a particular rite of passage in that particular niche of adventure. We become a part of a unique fraternity of like-minded adventurers.

It is as essential now as it always has been, for us as a species to continue exploring because there is always something our minds have yet to encounter. When framed this way, adventure is not a thing of the past after all, but a thing of the present and future. Experience and knowledge are the true infinite resources we can never fully exploit, and we live at an extraordinary time with extraordinary means of wandering. Take advantage of it. No matter how trodden the beaten path may seem, it still hasn’t seen your footprints.

For a lot of us, the monotony of modern life can result in bouts of depression, decreased sense of well-being, nihilism, and sheer boredom. We should not view these as light matters but as extremely consequential to our society. A recent nationwide survey of 20,000 Americans, in close alignment with previous surveys, found over 50% of respondents felt a variety of emotions ranging from feeling isolated or unwanted and having a sense that they lacked companionship, or that their relationships were not meaningful, thus indicating a rise in loneliness, especially among younger generations.

Some lean heavily on anti-depressants and other medications to overcome these negative emotions, while others turn to alcohol or illicit drugs. What a person could very well need to suppress such anxieties is embarking on their long-envisioned adventures. That might sound overly optimistic, perhaps naïve, and by no means is this meant to suggest a complete substitution for seeking professional help for serious mental and emotional issues. In my book, I explore more of the science and possible methods of alleviating mental disorders like depression and anxiety that involve immersing ourselves in natural landscapes.

In the meantime, we can at least begin to actively condition ourselves to view our world through a more adventurous lens. As Thoreau stated, “It’s not what you look at that matters, it’s what you see.” Adventure is dependent on your creativity and willpower.

Thanks for being a fellow traveler with me through this read. Please consider subscribing, sharing, and supporting this project. Much more to follow.

Cheers!

-JSB