Summoning the Anthropology of Wandering: A Primer to My Forthcoming Book

What is the anthropology of wandering? And can it guide us toward a more favorable view of humanity?

“It is important for us, humans, to be out there…we are an exploratory species, the last ten thousand years we’ve been sitting around in civilization, before that, for the last 100,000 years we were wanderers, explorers, nomads, and that is in our blood.”

-Carl Sagan

The anthropology of wandering sounds like a single topic, but it is many. In our sedentary “age of information,” we are overloaded daily by a tsunami of images, texts, and symbols, resulting in mixed feelings of anger, apathy, fear, uncertainty, and confusion. Many pages of ink have been spilled commenting on how we are “polarized” and “tribal” and suffering from a “crisis of meaning.” We can’t seem to find a way through the abyss of misinformation, cynicism, and nihilism that permeates much of modern life and culture. What’s more, few seem to be offering actionable solutions to combat these negative trends. What role might adventure play in alleviating these modern ailments?

I have coined the phrase “anthropology of wandering” as a field of study that explores the meaning of human travel and adventure. My research argues that an investment in travel and adventure has the potential to alleviate things like our culture of fear and cynicism and improve our well-being by exposing us to a far richer world than we find on television or the internet. Building on other social science research, it suggests that we require multiple vantage points to obtain some semblance of an informed worldview and to temper the darker forces permeating our culture and society.

In other words, we must be out wandering in the real world, coming face-to-face with a wide array of natural and cultural landscapes in order to fully appreciate the depth and complexity of our world. And travel and adventure—following our wanderlust—is a crucial way of optimizing a well-rounded view of our world. However, we must first learn how to encourage more of us to be out in the world with all our senses present and engaged in a realm of experiences that show us the true nature of our humanity, for we are plagued by many forces that constrain our movement: the structure of our sedentary society coupled with the overwhelming culture of fear from media and the psychological biases of our minds all operate together like a web to keep us in place.

The anthropology of wandering is a genre of research I’ve been developing since my time backpacking the Appalachian Trail in 2014. This research attempts to define what adventure and travel mean to societies and cultures across time and space and what lessons we may be able to learn from those who wander. For instance, when we examine the centuries of travel literature and art, accounts from holy pilgrimages, or statistics on modern tourism, we discover an impetus in many of us desiring to “see the world” for a variety of interesting reasons. What do we mean when we say we want to “see the world,” and why do so many of us have the urge to travel and explore the world in the first place? Where do these feelings arise in us, and how far back in time do they stretch?

Historically, we can review early travelogues too, like those we find in The Travels of Marco Polo or The Rihla by Ibn Battuta. We have early letters of some of the first accounts of climbing mountains like those of Francesco Petrarch’s ‘The Ascent of Mont Ventoux’ in the 14th century. We can also consult plenty of classic ethnographies, such as Bronislaw Malinowski’s Argonauts of the Western Pacific, whose notable subtitle was An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea. Furthermore, we can review recent data on travel patterns along with more recent studies in the anthropology of tourism, such as Hosts and Guests by Valene L. Smith, and the anthropology of adventure such as Tarzan was an Eco-Tourist…and Other Tales in the Anthropology of Adventure by Luis A. Vivanco and Robert J. Gordon.

This compilation of the anthropology of wandering I synthesize is therefore attempting to map out and answer a range of interrelated scholarly yet deeply existential questions around human travel and adventure:

Why do we travel and seek adventure?

When did humans first begin to explore the world for the sake of curiosity and discovery?

How do travel and adventure manifest in different cultures throughout history?

Why might varying societies encourage or prohibit travel and adventure?

What role does fear play in preventing us from experiencing travel and adventure?

What are the benefits and challenges of travel and adventure in the 21st century?

Where might the future of travel and adventure lead us?

When we pause for a moment and look around at our society, we see many kinds of examples of culture that compel us to “see the world.” The background on our computers is often filled with stock photographs of wonderful places around the globe. The documentaries and writings of David Attenborough, Neil deGrasse Tyson, Carl Sagan, and Jacob Bronowski charm us with musings and reflections on the cosmos and nature, urging us to see the grander picture outside our routine lives. What kind of meaning and benefits do we gain from “seeing the world?” And does travel and adventure—wandering, as I prefer it—enhance our empathy for humanity and perhaps have the capacity to reduce our fears and prejudices?

These are some of the core questions and considerations I explore in my forthcoming book An Anthropology of Wandering: How Adventure Can Alleviate a Fearful Culture.

Below is an excerpt from the book to be published later this year, and if you haven’t already, be sure to subscribe to receive more updates on the upcoming book!

Want more excerpts from the book?

The publication of An Anthropology of Wandering will be entirely self-funded, so any contributions to Those Who Wander will significantly help support my project. Please consider visiting the subscription options and upgrading to paid. Thank you in advance! Cheers!

There is no way to measure the loss of a grand experience not ventured. Individual lives cannot be science experiments. We cannot test out different life choices, then hit rewind and choose the best life course. Because of this, we often understandably choose the path of least resistance—“Better safe than sorry,” we too frequently say. What about the counterpart to this—“Nothing ventured, nothing gained?” How often have we all given in to a fear of some unknown adventure only to be plagued later by a tiny, disquieting feeling in our head telling us that perhaps we should have gone through with it? We all possess an adventure left untaken, unexplored, unlived. What exactly is stopping us from taking part in one of the most ancient and instrumental behaviors of our species—an intoxicating mix of serendipitous wondering and wandering?

The British travel writer Bruce Chatwin once sought to answer the question ‘Why do men wander rather than sit still?’ Why humans wander is also the central motif of this book, yet in our modern times, we are often restricted from pursuing our innate wanderlust. To my mind, we must first address the question of what holds us back from manifesting all those adventures we dream about. Ask yourself, is your life as adventurous as you’d like it to be? Chances are that the answer is a sheepish “no.” As untroubled children first eagerly learning to explore our environment, many of us dream of “seeing the world” when we get older, yet how many of us can confidently say, right now, that we’ve stayed true to this youthful yearning for adventure? Why did we have those dreams to trot the globe, to begin with? Was this simply a childish impulse or something deeper that we’ve learned in time to suppress?

As we age into adulthood, many things inevitably create impediments to our inherent wanderlust that make it challenging to sustain. Living in the fast-paced, status-seeking society that we do, we live under enormous social, cultural, and economic pressures to earn our keep, outcompete one another, and “maximize efficiency” from the cradle to the grave. We get caught up in the grind of our careers. We build families, communities, and businesses. We become tied to seemingly endless debts and responsibilities. If we are lucky and not tied too much to our work, we might have time to take our annual one-week vacation each passing year to destress and “recharge” as if we’ve become human batteries in the Matrix. However, we are certainly not immersing ourselves in the kind of travel and exploration many of us, I imagine, still desire to do “at some point down the road.” “Someday,” we say, but not now, not today. Is all this simply because this is just what growing up is—forfeiting things we want to do for things we have to do? Or is there something else happening to rationalize the abandonment of our adventures and creative outlets? What else might be going on to encourage our increasing passivity and sedentism?

The obstacle at the center of what prevents many of us from structuring adventure into our lives, one that we may not recognize or want to acknowledge, is fear. Fear manifests itself in various forms. We live evermore in a culture of fear and misinformation that subtly disorients us, heightens our anxieties, and prevents many of us from leading a more fulfilled and adventurous life. What if the source of alleviating many of our apprehensions about the world is paradoxically something we are afraid to do in the first place? Could adventure be an antidote to our modern unrest? And how do we begin to renew and restructure adventure back into our hectic modern lives?

I suspect there are many lessons that we can discover from those who wander, i.e., travelers and adventurers, that may enable us to overcome some of our major modern societal ailments—our fears, cynicism, anxiety, and disillusionment with humanity. I believe we must understand the origin of these deeply unsettling problems and what we can do to alleviate them, both at an individual and societal level. I also believe getting more of us to travel, experience, and appreciate adventure more qualitatively has a large role to play here. As the British author Alain de Botton wrote in The Art of Travel,

If our lives are dominated by a search for happiness, then perhaps few activities reveal as much about the dynamics of this quest—in all its ardour and paradoxes—than our travels. They express, however inarticulately, an understanding of what life might be about, outside of the constraints of work and the struggle for survival. Yet rarely are they considered to present philosophical problems—that is, issues requiring thought beyond the practical. We are inundated with advice on where to travel to, but we hear little of why and how we should go, even though the art of travel seems naturally to sustain a number of questions neither so simple nor so trivial, and whose study might in modest ways contribute to an understanding of what the Greek philosophers beautifully termed eudaimonia, or ‘human flourishing’.

Before we can learn why and how to wander and take our plunge into a renewed life of travel and adventure, it is important that we first understand the forces preventing us from doing so, and that will be the task of most of this book because, it turns out, it is as complex as it is fascinating.

Our shared outlook on the world is perplexing, to say the least. When we reflect on our contemporary society and gauge “the state of the world”, it’s not hard to sense the overwhelming weight of confusion, fear, alienation, and insecurity that persists within culture and society. But why is that? If we consult some of the general data and the researchers mapping out the trends of human development over the last few centuries, several of them seem to have nothing but good news to share that completely contradicts the horrendous narratives we endlessly hear on television or gawk at on the internet. The few researchers who compile and interpret this uplifting data inform us that we live in an astounding “age of information” with gadgets of unprecedented supercomputing power. We are incredibly privileged by the standards of human history. How do we explain this paradox, and what does adventure have to do with alleviating a culture of fear?

The anthropologist in me has a strong sense that a wandering ethos—an inner urge or calling to explore, if you will—to venture far and wide is a deeply embedded feature of our humanity and one that has played a vital role in our evolution and survival as a species. From my study of hunter-gather societies, I believe, as Bruce Chatwin did, that “evolution intended us to be travellers” and that “we are travellers from birth.” Much travel literature often describes adventurers’ reflections on their soon-to-be travels in similar poetic musings. The 14th-century traveler Ibn Battuta, upon departing for his initial 3,000-mile hajj or pilgrimage from his hometown of Tangier to Mecca, described his original yearning for the adventure to come as being “swayed by an overmastering impulse within me and a desire long-cherished in my bosom to visit these illustrious sanctuaries.” What exactly is it that captures and has captured the minds of so many wayward travelers, nomads, pilgrims, and explorers throughout history? Is this a shared human universal or present in only a select few restless risk-takers?

As a social and cultural phenomenon, we’re incredibly fascinated by mythical tales and stories of adventure and the wanderers of each passing generation—from Odysseus to Robinson Crusoe, from Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo to Lewis and Clark, from Amelia Earhart to Yuri Gagarin. We’ve likely been entranced by these legendary figures since time immemorial—predominantly living as hunter-gatherers, nomadic herders, and agriculturalists. Although a vast number of our species now live in a sedentary industrial society, some of us still manage to pursue this wandering ethos in diverse and creative ways.

Regrettably, this human behavioral trait and cultural expression of wandering is rarely a subject of modern anthropological discussion (even though it is the basis for why so many anthropologists get involved in the study of anthropology in the first place). Indeed, the motto of anthropology could very well be that we desire to see the world through another’s eyes. This anthropological longing for perspective is the same for the world traveler and seeker of adventure. I have therefore summoned this phrase of the “anthropology of wandering” to pursue the questions related to human wandering across time and space.

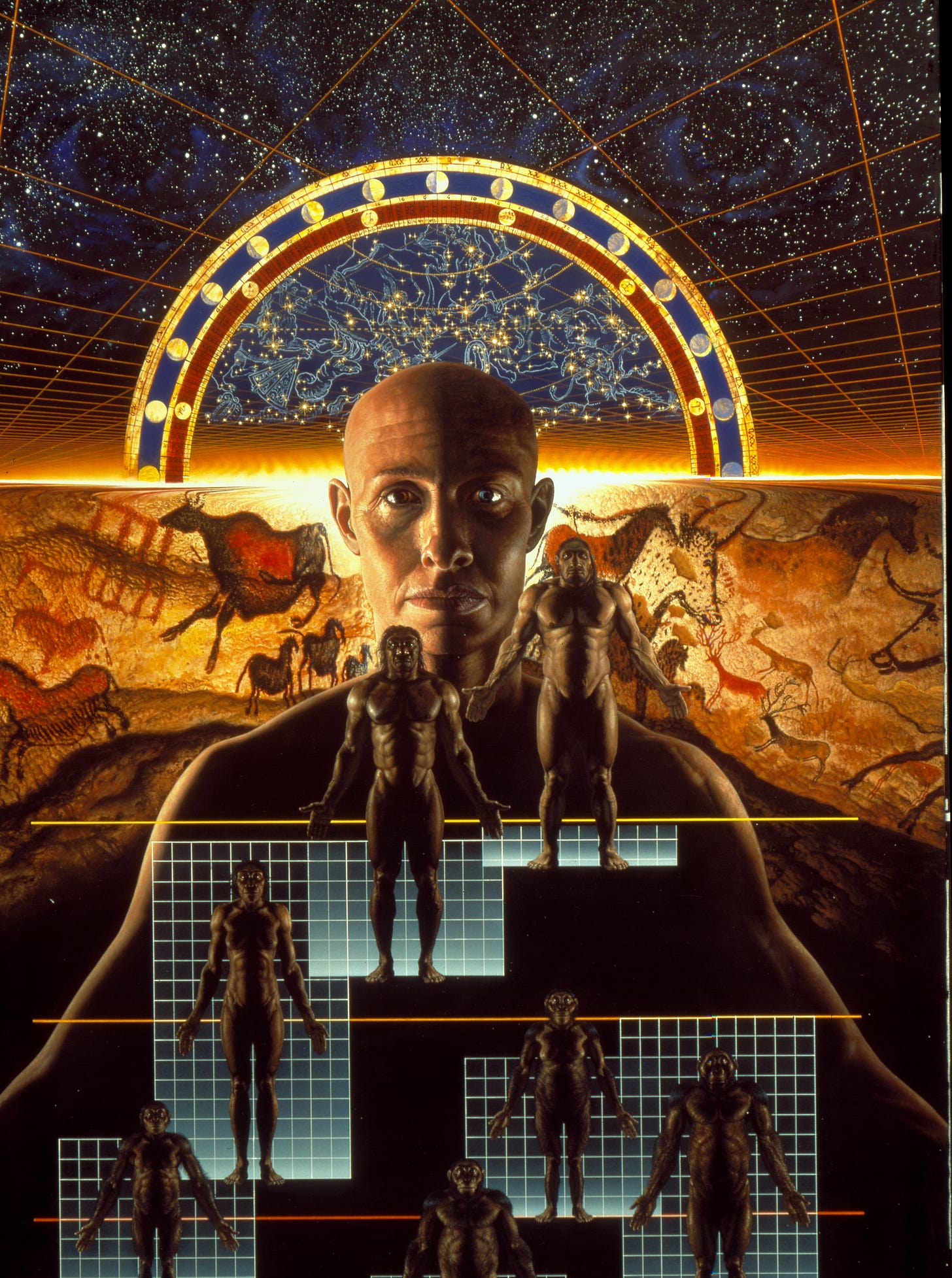

Many anthropological questions align with adventure and are left open for us to contemplate. For instance, at what point in time did the spark to venture out beyond the horizon arise in human consciousness? Did Homo ergaster or Homo erectus—archaic forms of humans known as hominins living in the middle Pleistocene some 1.5 to 2 million years ago—share the same restive urge for adventure as us? Were they also compelled to see how far the land goes that wasn’t just inspired by a mere craving for food? What exactly is this “wandering ethos” or sense of adventure that compels us to move and explore our environments? Don’t you ever get restless and bored staying in one place for very long?

The ability to wander has been a deep feature of our humanity for quite a long time with many cultural manifestations across the millennia, likely among several different hominin species, beginning with the evolution of bipedalism, dating to at least 4.2 million years ago.

We often get itchy feet to go and do something different. Where does that feeling come from, and why aren’t we all content to just sit on the couch all day? Is a desire to wander not another plausible hypothesis to entertain and explain why our human presence is now global? Nearly all species of the earth with the ability to locomote will explore their environments for a variety of reasons. But at what point in our human lineage did we gain the capacity to wonder about wandering to foreign and distant places? Were certain individuals in our nomadic hunter-gatherer days selected to search for new source materials for their tools or find other groups to trade with, all based on their eagerness for adventure? What role might this have played in our evolution? These questions are almost certainly beyond proper scientific hypothesis testing, yet they are still philosophically worth pondering nonetheless, are they not?

It isn’t hard to imagine our earliest hunter-gatherer ancestors reminiscing around a blazing fire about their celebrated explorers who led their great-great-grandparents to greener pastures teeming with game and abundant resources. Perhaps they immortalized them in some form on indecipherable cave paintings or etched them into sandstone petroglyphs on one of the tens of thousands of archaeological sites spread across the globe. We find the occasional commentary on the subject of adventure from classic ethnographies from such notable anthropologists as Bronislaw Malinowski, A.R. Radcliffe Brown, Margaret Mead, Ruth Benedict, or Claude Lévi-Strauss.

Thus, our urge to wonder and wander runs very deep in who we are as a species. Modern life has a wonderful array of benefits, but some things are out of line with how we’ve evolved. There still is a lot to understand, but cognitively, at some point we evolved a unique capacity to not just remain in a single habitat like most species but to move to and explore all areas of the globe. This deep, restless yearning to toss ourselves into the wild unknown certainly must have found cultural expression long before such adventurous tales as the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Iliad, and the Odyssey were written down. The way some of the earliest poems were written and echoed by bards draped in himations (Romans invented the true toga) hints at a much longer tradition of remembering and transmitting stories orally. We’re naturally intrigued and perplexed by those who seem to willingly place themselves at risk for the mere sake of it. Why leave the comfortable abode of our homes? What could possibly be gained from throwing ourselves so aimlessly into bizarre, uncomfortable, and unknown situations?

End of excerpt.

Now, is encouraging more people to jump on planes powered by fossil fuels to touristify all the quaint destinations of our world truly such a wise thing anymore? I understand the many challenges associated with encouraging more people to travel nowadays. We face significant ecological, political, economic, social, and cultural problems when it comes to the mass movement of people in the 21st century. However, my arguments for the need for more of us to structure travel and adventure into our lives are more elemental than this. A lot of my outlook on the world comes from the considerations of a style of anthropology that offers a perspective that takes the long view of humanity, sometimes millennia long, and it can be difficult to get this point across. Most of us do not think in long time spans like geologists and cosmologists, so I understand why anthropologists and archaeologists often come across as out of touch with people today because we are, by definition, out of touch, and that is not necessarily a bad thing…not always anyway.

Making travel and adventure a more common experience is a net positive if done right. Now I know that is a big if in a lot of people’s minds because we can also be a thoroughly careless and capricious species as well, but the alternative of people staying put, not experiencing other areas of the world, and not recognizing all the benefits travel and adventure offer is also bad, not the least of which is what Mark Twain famously and poignantly opined,

Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts. Broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things cannot be acquired by vegetating in one little corner of the earth all one's lifetime.

And so, I believe the first task at hand is demonstrating why adventure matters and how our culture can better value it, and secondly, how, as a society, we make adventure more common and accessible to more of us.

The anthropology of wandering, therefore, attempts to be as wide and as encompassing as possible as it tries to speak to the human zest for exploring. It considers the long literature of adventure from the Epic of Gilgamesh across the centuries to the Odyssey and on up to our present day with Bill Bryson’s A Walk in the Woods exploring backpackers on the Appalachian Trail. We consider religious pilgrims and trade networks like the Silk Road. The list of characters in this story is long: pilgrims, vagabonds, merchants, explorers, tourists, researchers, scientists, hitchhikers, backpackers, mountain climbers, and deep-sea divers are only a fraction. And this subject extends far back in time to considerations of human origins with new genetic evidence on human movement and settlement, of our evolution with the first hominin to leave Africa, Homo erectus, and to future considerations of wandering on other planets and the kind of future of adventure and travel that still awaits us on this planet.

My current project, then, is an attempt to summon this anthropology of wandering because I sense that structuring adventure into our society, culture, and personal lives can serve as a powerful antidote to the fear, cynicism, misanthropy, and “crisis of meaning” plaguing many of us in the modern world. Therefore, engaging with the world with all our senses present and learning how to see this world from many vantage points is what will enable more of us to appreciate the human condition and is one of the greatest gifts the anthropology of wandering can offer us.

Thanks for being a fellow traveler with me through this read. Please consider subscribing, sharing, and supporting this project—much more to follow.

Cheers!

-JSB

I saw an excellent documentary on Aborigines and their ramblings---which the doc explained was often to escape others living too near them. I'd love to watch it again but can't recall the title. A friend worked with them years ago while she was working in a university (think near Melbourne) where she'd go into the field and tried to set up a library (!) for the Aborigines (I'd always thought their communication was without writings. It sounded fascinating and she did it for about 3 years. She always takes on unbelievable tasks, that tend to be fascinating.

Justin, I look forward to the book. Have you ever wondered if members of more nomadic Native American tribes were happier than members of less nomadic tribes? Or, in more general terms, all other things being equal, is the hunter following the game happier than the farmer tending the crops?