Dublin and Its Environs: A Walker’s City and the Weight of History

The capital of Ireland, like most old cities, is a palimpsest of history. Walking its streets and the city's outskirts provides one a remarkable opportunity to unpack its many layers of the past.

“There was a lust of wandering in his feet that burned to set out for the ends of the earth. On! On! His heart seemed to cry. Evening would deepen above the sea, night fall upon the plains, dawn glimmer before the wanderer and show him strange fields and hills and faces. Where?

-James Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

In an introduction to James Joyce’s short stories, Dubliners1, we learn that the capital of Ireland was once referred to as the “second city of the British empire” but it was also dubbed a “walker’s city.” As I found myself alone for a week-long trip there, I planned to do plenty of walking in the “walker’s city” and test how true that moniker still was. Like many other old cities, Dublin was born organically to accommodate the pedestrian way of life long before industrialization coughed up cars, trains, buses, trolleys, and trams. City planning and urban sprawl eventually began to accommodate the automobile over human feet. For centuries, everything was built to be accessible on foot or by horse: the market, the church, the town square, the graveyard.

Walking the streets of modern Dublin, one is immediately struck by the ancient remnants of the past—a palimpsest of history surrounds you. Collectively, the buildings are a patchwork of medieval Gothic, Neoclassical, Edwardian, Georgian, Victorian, and modern styles. Wandering around, reading the plentiful plaques across the cityscape, and perusing museums allows one to unpack the many layers of the past. With no one else to coordinate my loose itinerary with, I was granted a rare opportunity to lose myself in the depths of Ireland’s rich, albeit grim, history for a whole week—a crash course of nearly 10,000 years of prehistory and history I only briefly glimpsed but gratefully cherished.

I didn’t begin my historical overview of Ireland in Dublin. First, I trekked outside the city on my first full day to take a step far back in time to the Neolithic period (4,000-2,500 BCE) and visit the ancient monuments of Newgrange (Sí an Bhrú in Gaelic) and the Hill of Tara (Teamhair or Cnoc na Teamhrach in Gaelic), both approximately an hour northwest of Dublin. These sites have played an outsized role in the prehistory of Ireland, being major centers of social, political, and religious activity from the Neolithic era up through the Bronze and Iron Ages. In the early 20th century, part of the Hill of Tara was damaged–marked by several acres of uneven ground–by British Israelites who came searching for the Ark of the Covenant. One hundred and forty-two kings are said to have been crowned on the Hill of Tara and many legends and myths were born here.

Those of us conscious of modern geography may be surprised to know that the first people arrived in Ireland by walking. They followed on the heels of retreating glaciers approximately 16,000 years ago, toward the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, by walking across a land bridge of ice still connected to Eurasia's mainland. There is growing archaeological evidence suggesting people made it to Ireland much earlier, such as a cut reindeer bone analyzed in 2021 dating to around 33,000 years ago. Also, the archaeology museum at the National Museum of Ireland houses manipulated flint cobbles dated between 300,00-400,000 years ago that may indicate earlier forms of humans present on the Irish landscape, such as Neanderthals or members of the species Homo heidelbergensis (both extant in Europe at the time). However, only closer to the end of the Ice Age do we see evidence of a larger influx of paleolithic hunter-gatherers wandering into the Emerald Isle, not unlike how the initial inhabitants wandered into the Americas around 15,000 years ago. Paleolithic and Mesolithic, peoples traversed across the Eurasian landmass during multiple migration periods and found a thickly wooded landscape of dense conifers, tundra, bogs, and large game such as reindeer and the famed Irish elk, along with other megafauna still extant at the time.

Then came the Neolithic period around 5,000 years ago which witnessed gradual waves of peoples from Eurasia, especially from the Middle East and southern and eastern Europe. They brought farming, ceramics, and a knack for megalithic mound construction as seen at places like Newgrange and the Hill of Tara and other mound centers throughout the Boyne Valley (Brú na Bóinne). By around 3,700 BCE, the new farmers had largely displaced the hunter-gatherers and significantly modified the landscape as they cleared forests to make way for agriculture and growing settlements.

The inside of the passage tomb of Newgrange feels much like being in a cave and one is astounded to find that you are standing in a structure older than the Great Pyramids in Egypt and Stonehenge. The cool dry air has a calming effect and standing within the main chamber of one of the oldest standing structures in the world and staring up at a ceiling of boulders that’s been intact for 5,200 years is an indescribable feeling. At one point, the archaeologist who led our tour shut off the lights and recreated via a simulation of artificial light what takes place here on the winter solstice: A rising sun casts beams of light that filter in through the “roofbox” toward the entrance, which then illuminates the interior of the chamber for only a few minutes on that single morning day in December. Ancient peoples buried their dead here after cremation. It is suspected this meticulous astronomical engineering played a large role in their religious rituals, perhaps an intricate attempt to shine light on the dead as a monumental gesture of remembrance.

The following day, I spent a large portion of the morning and afternoon wandering through the archaeological exhibits in the National Museum of Ireland perusing the entire ground floor of the museum displays of artifacts from the Paleolithic period up to the time that Vikings from Norway arrived on the Emerald Isle at the end of the 8th century AD and the Anglo-Normans invaded at the end of the 12th century. The upper floor houses exhibits on the Vikings and the Medieval period in Ireland. Some of the most incredible finds in Ireland have been retrieved from the spongy freshwater bogs which serve as remarkable time capsules, preserving everything from hoards of gold cached there during the Bronze and Iron Ages to textiles to individuals, many of whom suffered horrible instances of violence. The famed “bog bodies” of Western Europe are a remarkable, albeit morbid, glimpse into the world of sacrificial and ritualized violence.

The middle of my week was devoted to wandering more of Dublin, all the while sampling a variety of Irish whiskeys and the abundant cafes dispersed across the city. I ambled around the public park of St. Stephen’s Green and discovered one of the many memorials strewn across the cityscape that are dedicated to Joyce. It is noteworthy that Dublin pays homage to so many literary icons from Joyce to W.B. Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, Samuel Beckett, Oscar Wilde, Bram Stoker, Seamus Heaney, and Jonathan Swift. A memorial wall known as the “Literary Parade” that abuts Saint Patrick’s Park adjacent to Saint Patrick’s Cathedral also celebrates the literary achievements of Irish authors.

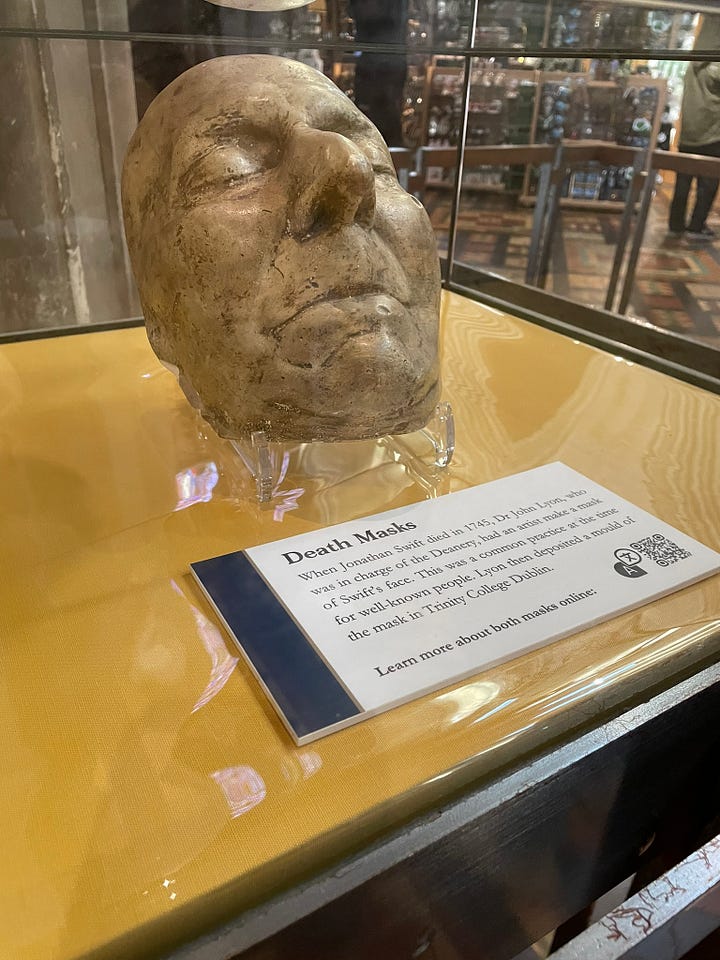

Speaking of Jonathan Swift, he is buried within the floor of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, another monumental masterpiece that will inspire you regardless of whether you are religious or not. They have casts on display of his death mask and skull which was a common practice during the 18th century for famous figures when the pseudoscience of phrenology was all the rage. These rather macabre practices once hoped that the shape of the skull could be examined to reveal insights into a person’s character.

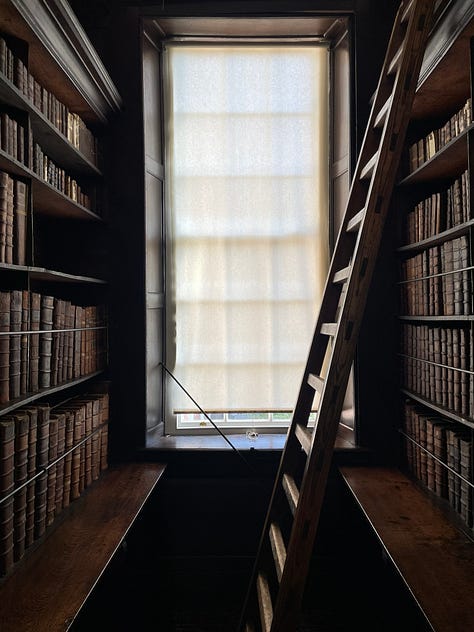

Following the wrought iron gates along the southern façade of the cathedral and the bend of the road of St. Patrick’s Close led me into an unassuming 18th-century brick building that contained one of the most remarkable collections of some of the oldest printed books in the world. Marsh’s Library is Ireland’s first public library, opened in 1707, and it is a bibliophile’s shrine, housing thousands of books and manuscripts from the 15th to the 18th centuries. Marsh’s Library is undoubtedly one of the most enchanting places I’ve ever encountered.

My final day in Ireland took me back outside the city. I traveled south of Dublin with a brief stint in the Wicklow Mountains and then stopped at the early medieval monastery of Glendalough, an early Christian settlement founded by Saint Kevin in the 6th century AD and located an hour southwest of Dublin. Glendalough is an idyllic location situated in a valley with two lakes and the crisp fall weather gave a similar calming sense to that I felt while at Newgrange.

I had time to hike past the lower lake to a waterfall and stand on the shores of the larger Upper Lake. The place was tranquil and I could instantly see why monks would want to cloister themselves away from the grim dark ages and worship in a sanctuary like this. However, the place was not immune from violence, as it was raided multiple times in later centuries by those seeking valuables and important relics that are said to have been stashed here by the monks.

A final stop took me to the medieval town of Kilkenny, the crown jewel of the place being Kilkenny Castle which flanks the River Nore. The invading Normans constructed it in the early 13th century and it has largely stood the test of time. However, the eastern wall and one of the towers were destroyed during Oliver Cromwell’s conquest of Ireland during the siege of Kilkenny in 1650, one of many violent upheavals in Ireland’s long history.

I wanted my trip to be as minimalist and simple as possible and thus I chose to walk as much as possible. I didn’t want to make too many plans ahead of time and just wanted to allow the city and its environs to pull me along. I was not disappointed by this approach.

I hadn’t read any Joyce before I booked my trip to Dublin but in the months leading up to my one-week stint here, I tried my best to do justice to his works—I read his short stories Dubliners, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and made it through the first 100 pages of Ulysses before setting it aside out of sheer exhaustion. Even for an avid reader, Joyce is challenging to read, but what I love most in Joyce is what I loved in Dublin: The characters walk, albeit by necessity because most of them are impoverished, but this forced experience to walk enables a certain way of engaging with the world—one that ends up unsuspectingly benefiting us even if we’d much rather take a bus or a cab nowadays.

This dominant social reality of having to navigate the place you inhabit on foot is what connects us to most other times and places in human history—the weight of history can be felt whether you are walking through a modern city, a museum, or an ancient archaeological site. Though the city is a recent human creation relative to the entire breadth of human history, it is nonetheless a space that requires an investment of time for us to traverse it. By my estimate, we come to understand a place best when traveling through it at about three miles an hour.

One of my favorite excursions while in Dublin was taking a James Joyce walking tour led by the James Joyce Center. Although the day was gloomy and a mist of rain peppered us the entire 2.5 hours, it was a wonderfully informative tour of the history and literature of not only Joyce but the city of Dublin along with many of the famed canon of Irish authors. Joyce famously used Dublin as a template for many of his stories and one comes to better appreciate his challenging prose while walking in the footsteps of the places he meticulously described.

Today, it is challenging to imagine a world where everyone walks. To those of Joyce’s time, it would have likely been absurd to most people for someone to take an interest in walking. Walking is something we either look at in dismay that everyone was forced to walk everywhere or, for the few romantics like me, wonder if perhaps that’s how things ought to be. I do not doubt that we gained much progress through all the transportation technology we’ve inherited but there’s been something assuredly lost as well, to my mind at least. As Rebecca Solnit, author of Wanderlust: A History of Walking, observed,

Many people nowadays live in a series of interiors—home, car, gym, office, shops—disconnected from each other. On foot, everything stays connected, for while walking one occupies the spaces between those interiors in the same way one occupies those interiors. One lives in the whole world rather than in interiors built up against it…exploring the world is one of the best ways of exploring the mind, walking travels both terrains.

It is difficult to articulate this sentiment to those of us who would hate living in a world where getting across town would take half the day or visiting relatives in the next county would take a serious investment in planning. And when I’m not in a romantic stupor, of course, I wouldn’t want to walk everywhere either. I realize the absurdity of this in our modern age. Nonetheless, I still contend that we have a right to slow down and ought to embody the case for slow travel.

I cannot help but wonder: How much did people living in all these other eras before our fast-paced society started filling us with anxiety take this feature of their world for granted; that there was something idyllic and social and wonderful that everyone had to move across the landscape so slowly—the poor as well as the rich. To me, there will always be something enchanting and rejuvenating about taking random unplanned walks.

Things are always changing. The Dublin of the 10th century is not the Dublin of the 12th century, is not the Dublin in the early 21st century. What is refreshing and remarkable is that Dublin remains a walker’s city despite all the changes it has adopted over the centuries as history swept over it. The proper understanding of a place begins with its history or some semblance of it. We are limited in our capacity to fully understand history, but we can nonetheless take the journey to acquire a better, more meaningful sense of it. I attempted this in Ireland and only scratched the surface, but I came away with a renewed appreciation for yet another place on the globe I could only momentarily inhabit.

I love all things eclectic. I think that’s what modern Dublin embodies, and so does its past. You will hear an endless variation of languages as you wander the ancient streets. Ireland is not known for having a particularly diverse cuisine. It’s a meat and potatoes kind of place, but in recent years there has been a kind of culinary renaissance coming from the continent which is noticeable today—Parisian, Tuscan, Norwegian, Anatolian. Each building is from a different century with decades of modifications selectively altered with each passing year—a window or entryway is now a layer of bricks. It is a bustling place with so many walking to and from work—interestingly most of the vehicles on the road in the inner city seemed to be buses, cabs, and Uber drivers.

Ireland is not a place without problems, certainly in its past, but also in its present. Housing and immigration have become major political problems, as they are in many European countries. But Ireland is a resilient nation. Gauging by its grim past, it has steadily ambled through many troubling eras—from the ancient days of ritualized violence to civil wars, revolutions, famines, plagues, extreme economic instability, and religious sectarianism. Our tour guide to Glendalough and Kilkenny was only half-joking when he said “In all the 8,000 years of Irish history, only the last 25 years have been prosperous and peaceful!” As if to solidify his point (and in characteristic Irish fashion), he sang the sorrowful yet beautiful ballad “The Fields of Athenry.” Ireland has certainly not made it to the present unscathed but somehow, at least for the moment, appears better off and enriched—and walking this city allows you to feel the weight of that history.

Thanks for being a fellow traveler with me through this read. Please consider subscribing, sharing, and supporting this project—much more to follow.

Cheers!

-JSB

James Joyce, Dubliners, New York: Penguin Books, 1992.

Gosh this makes me want to visit, and walk around, Dublin all the more. 🙂 So much to take in…!

I really enjoyed reading your article, Justin. I hate to admit it, but in the five years my husband and I have lived in Ireland, we still haven't managed to visit Newgrange. (But it is high on my list.) I love the National Museum of Ireland--there are so many fascinating artifacts among its collections. I also love the Trinity College Library, but I had never heard of the Marsh Library--so I have put that on my list as well. And I am really glad you made it to Kilkenny, which is my favorite town in eastern Ireland. I also agree with you about the joys of walking!